About

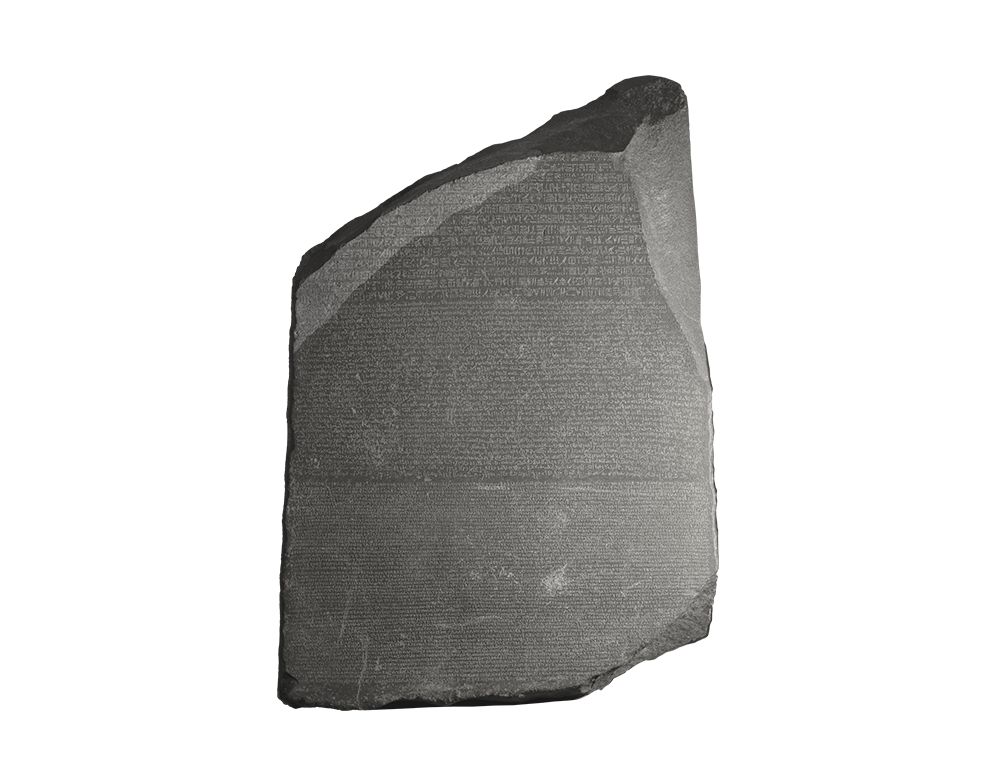

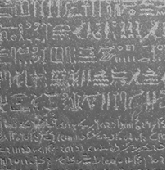

The goal of the Digital Rosetta Stone project is to create digital data for teaching and research. The Rosetta Stone contains three versions of the same decree in ancient Egyptian and ancient Greek, inscribed in the Hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek writing systems. These features, along with the importance of the stone, are proving to be very effective for teaching historical languages and digital humanities in an interdisciplinary environment. They also present fascinating challenges for digital humanities research in preserving historical scripts and extracting linguistic data.

For all of these reasons, the Digital Rosetta Stone project has engaged researchers and students to take new photographs of the Rosetta Stone and produce new digital data for experiments in image visualization, text-image alignment, and linguistic annotation. Data and results of the Digital Rosetta Stone project have been used to teach students in Egyptology, Classics, and Digital Humanities at Leipzig University and to train students and colleagues at other institutions. For more information, please visit the old project page at rosetta-stone.dh.uni-leipzig.de and our virtual exhibition (in English and German) at the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek providing further resources such as links to videos from teaching (e.g. for the Sunoikisis Digital Classics online study program) and publications.

The Rosetta Stone

The Discovery

The Rosetta Stone was found near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Delta of the Nile in July 1799 by the French officer Pierre-François Bouchard during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt.

The Decipherment

With the help of this tri-scriptual decree and other sources, Jean-François Champollion was able to decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs back in 1822.

The Preservation

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous rocks of the Ancient World and is on display in the British Museum in London.

The Rosetta Stone and Leipzig

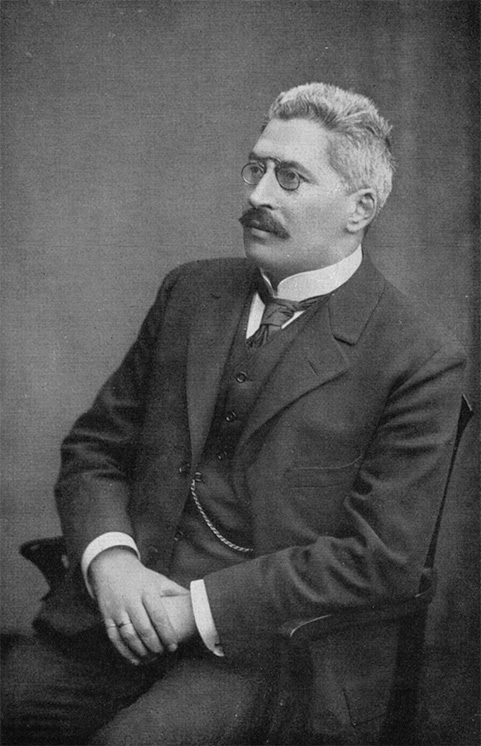

Georg Steindorff (1861–1951), a professor of Egyptology at the University of Leipzig (from 1894), once attempted to bring a copy of the Rosetta Stone to Berlin with the assistance of Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, then a curator at the British Museum. While in London, Steindorff made inquiries regarding this plan. However, the endeavor was never realized. How do we know this? The evidence comes from letters Steindorff wrote from London to his mentor and superior at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, Adolf Erman.

At that time, Steindorff was working as Erman's assistant alongside the papyrologist Ulrich Wilcken—a collaboration that was widely regarded as a "dream team." In the archives of the Egyptian Museum of the University of Leipzig (ÄMULA), a letter dated November 10, 1892, reveals that Steindorff informed Erman of Budge's approval for Berlin to receive a plaster cast of the stone and a Middle Kingdom head. However, no further details are available in the archive.

Interestingly, rumors persist to this day that Leipzig University possesses a copy of the Rosetta Stone. Nevertheless, it can be definitively stated that no such plaster cast exists. That said, the Institute of Near Eastern Studies and the Museum of Classical Antiquities at Leipzig house many replicas from the ancient world.

Our German translations of the Rosetta Stone’s Hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek inscriptions were inspired by the work of Heinz-Josef Thissen (1940–2014), a professor at the Seminar for Egyptology at the University of Cologne. Thissen’s academic legacy, including his extensive Egyptian and papyrological library, was bequeathed to the Egyptological Institute of the University of Leipzig. During his career, he maintained strong ties to Leipzig, collaborating with numerous colleagues on various projects and co-supervising many Leipzig scholars during their doctoral or habilitation studies. Among his mentees were Ludwig Morenz, Tonio Sebastian Richter, Lutz Popko, Katharina Stegbauer, and Franziska Naether.

While he was alive, Thissen generously shared his work on the Rosetta Stone with the Leipzig academic community, for which he is deeply appreciated. We strive to honor his legacy and contributions to the field.

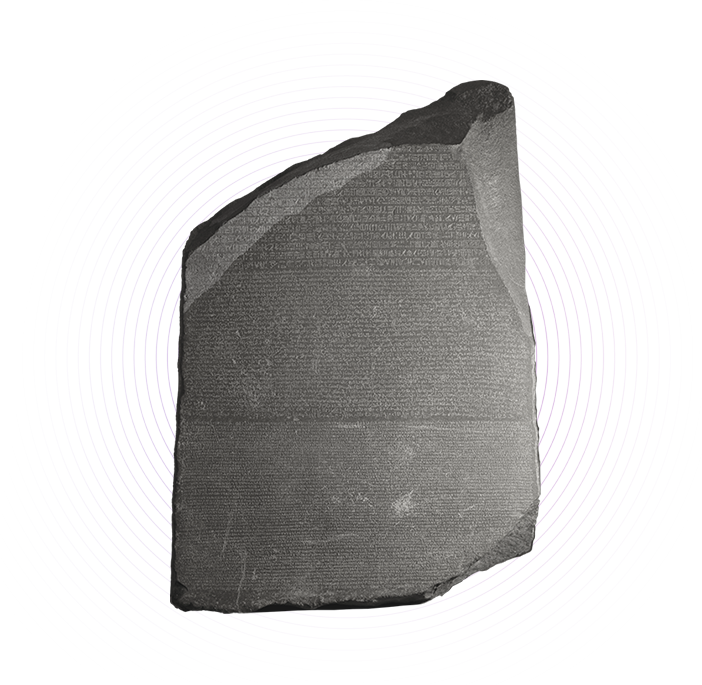

Images

Thanks to the collaboration with the Digital Epigraphy and Archaeology Project at the University of Florida, the team of the Digital Rosetta Stone Project took new pictures of the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum in June 2018 with the shape-from-shading technology (3D). These images are now available in a GitHub repository under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

These photographs were used to produce the following outputs:

- Visual Alignment. A text-image alignment by Mirian Amin and Josephine Hensel at Leipzig University to navigate the Rosetta Stone and visualize the corresponding text. For more information, please read the How To.

- Depth Map of the Rosetta Stone. An artifact that depicts the depth map of the Rosetta stone, which was algorithmically generated by Angelos Barmpoutis and Eleni Bozia at the University of Florida.

- Rosetta Stone Images Compare. A tool to compare a high resolution photo and the depth map of the Rosetta Stone.

Data

A new digital text of the Rosetta Stone has been created to generate different outputs:

- Textual Alignment. The three versions of the Rosetta Stone and the German translation have been aligned by Josephine Hensel using the Ugarit iAligner.

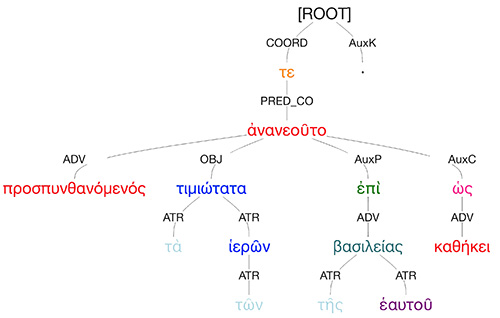

- Treebanking. The ancient Greek text of the Rosetta Stone has been linguistically annotated by Polina Yordanova using the annotation tool Arethusa. Josephine Hensel is currently working on the linguistic annotation of the ancient Egyptian texts of the Rosetta Stone.

- DFHG - Marmor Rosettanum. Digital version of the Greek text of the Rosetta Stone as part of the Digital Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum (DFHG) project.

Publications

Miriam Amin, Angelos Barmpoutis, Monica Berti, Eleni Bozia, Josephine Hensel, Franziska Naether. "The Digital Rosetta Stone Project". In Rita Lucarelli, Joshua A. Roberson, Steve Vinson (eds.). Ancient Egypt, New Technology. The Present and Future of Computer Visualization, Virtual Reality and Other Digital Humanities in Egyptology. Leiden: Brill 2023, 58-84. DOI: 10.1163/9789004501294_004.

Monica Berti and Franziska Naether. "The Digital Rosetta Stone". In Ilona Regulski (ed.). Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt. London: The British Museum 2022, 236-241 (Exhibition link).

Miriam Amin, Monica Berti, Josephine Hensel, Franziska Naether. "The Digital Rosetta Stone Project". In Mario Capasso, Paola Davoli, Natascia Pellé, (eds.). Proceedings of the 29th International Congress of Papyrology. Centro di Studi Papirologici dell’Università del Salento: Lecce 2022. DOI: 10.1285/i99788883051760

Monica Berti. "Digital Rosetta Stone". In Monica Berti. Digital Editions of Historical Fragmentary Texts. Heidelberg: Propylaeum 2021, 299-304. DOI: 10.11588/propylaeum.898.

Miriam Amin, Angelos Barmpoutis, Monica Berti, Eleni Bozia, Josephine Hensel, Franziska Naether. "Depth Map of the Rosetta Stone". Gainesville-Leipzig 2018. DOI: 10.17613/t1e2-0w02.

Exhibits

Digital Exhibition of the Rosetta Stone by Franziska Naether: Aller guten Dinge sind drei / All Good Things Come in Threes (in German and English). See also the release report by the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

3 July to 11 September 2022, Museum für Druckkunst Leipzig: Neue Wege zu alter Weisheit. Hieroglyphen im Buchdruck & 15 July to 13 November 2022, Egyptian Museum of Leipzig University: Neue Wege zu alter Weisheit. 200 Jahre Entzifferung der altägyptischen Hieroglyphen, press report from the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

13 October 2022 to 29 January 2023, British Museum London: Hieroglyphs: unlocking Ancient Egypt, exhibition website.